|

|

|

|

|

Archaeology

Project

|

|

|

Part 3.

When Was the Compound Occupied?

Archaeologists

use several methods and types of evidence to determine when a site was

occupied, including stratigraphy, typology, and explicitly dated materials

(coins, texts). In addition, carbon-14 tests can be used on organic materials,

such as parchments (animal skins).

Archaeologists

use several methods and types of evidence to determine when a site was

occupied, including stratigraphy, typology, and explicitly dated materials

(coins, texts). In addition, carbon-14 tests can be used on organic materials,

such as parchments (animal skins).

Stratigraphy

is the analysis of a sequence of layers, buildings and other features

of a site. Archaeologists dig trenches to expose the features of a site,

and then use that initial sounding to follow the walls and cavities

that they discover. The presumption is that higher layers represent

later occupations, although there can be complications (as when a garbage

pit is dug, or when ancients transferred "rubble" from one room to another

space).

Typology

refers to the study and classification of certain artefacts that can

be grouped together because they share important characteristics. Examples

would be ceramic or pottery, glass, textiles, and tools. Within a given

category, analysis can determine the geographic origin and rough date

of a given piece.

Explicitly

dated materials include coins most commonly, but can also include

what are called "documentary texts," which are deeds of sale, rental

contracts, I.O.U.'s, marriage contracts, or deeds of gift like the ostracon

(inscribed piece of pottery) to the right. Ancient coins were stamped,

as ours are, with dates, although not with absolute dates, since there

was no universally agreed-upon calendar. Rather, the date would be "year

'x'" of a particular ruler's reign. Documentary texts, for their part,

begin with a date clause which also indicates "year 'x'" of someone's

rule. The date clause in the deed to the left is "In the first year

of...," probably in the first year of the liberation of Israel, that

is, the first year of its revolt (66 C.E.). When these

kinds of documents are found in a particular stratum, that stratum can

be dated with some confidence. Explicitly

dated materials include coins most commonly, but can also include

what are called "documentary texts," which are deeds of sale, rental

contracts, I.O.U.'s, marriage contracts, or deeds of gift like the ostracon

(inscribed piece of pottery) to the right. Ancient coins were stamped,

as ours are, with dates, although not with absolute dates, since there

was no universally agreed-upon calendar. Rather, the date would be "year

'x'" of a particular ruler's reign. Documentary texts, for their part,

begin with a date clause which also indicates "year 'x'" of someone's

rule. The date clause in the deed to the left is "In the first year

of...," probably in the first year of the liberation of Israel, that

is, the first year of its revolt (66 C.E.). When these

kinds of documents are found in a particular stratum, that stratum can

be dated with some confidence.

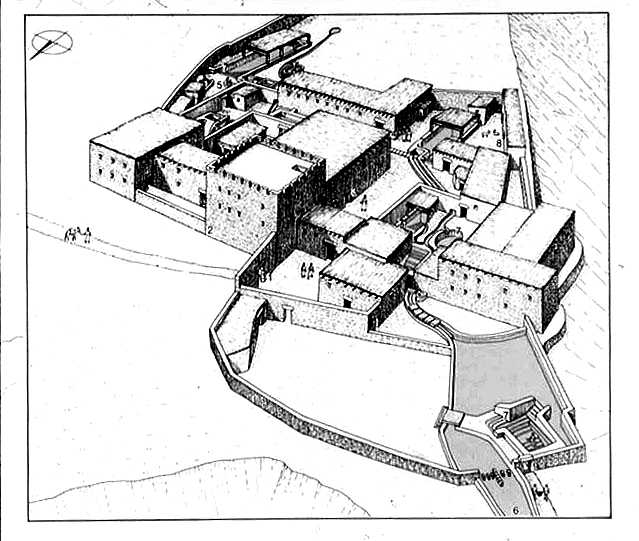

Together,

this evidence can yield the history of a site's occupation, though since

evidence can be read several ways, archaeologists are under a special

obligation to publish a final report detailing their excavations. That

was never done for the Qumran site, so the following evidence will be

derived from De Vaux's preliminary reports, VanderKam pp. 22-3,

and the Magness

article you read.1

Evidence

& Questions

This part

of the project will focus on the coin evidence, since it was central

to De Vaux's determination of the chronology of the settlement and because

the dates are pretty straightforward.

De Vaux

found coins ranging in date over a 355-year period, as illustrated in

the Table below. He had other evidence to help interpret the coins,

such as the stratigraphy of their location. But you have much of his

evidence in the chart below. Your job will be to review the Table and

reconstruct the history of the settlement based on the evidence.

Coin or

numismatic evidence is a little tricky. By virtue of its dates, it gives

us the terminus post quem, or earliest date that the coin could

have appeared at the site; a coin minted in 100 B.C.E.

could not appear at the site before that date. But the coin could

have appeared at the site as long as it was in circulation, and we usually

don't know how long a period that was for most coins.

| Year |

Government |

Ruler/Year |

Evidence

from Qumran |

|

223-187 B.C.E. |

Seleucid (=Greek) |

Antiochus III |

1-2 bronze |

|

175-164 B.C.E. |

Seleucid (=Greek) |

Antiochus IV |

1-2 bronze |

|

145-139 B.C.E. |

Seleucid (=Greek) |

Demetrius II |

1 silver |

|

139/138-129 B.C.E. |

Seleucid (=Greek) |

Antiochus VII |

3-5 silver

1-2 bronze |

|

134-104 B.C.E. |

Jewish |

John Hyrcanus |

1 coin |

|

126-9/8 B.C.E. |

Tyrian |

/// |

561 silver tetradrachmas |

|

104-103 B.C.E. |

Jewish |

Aristobulus |

1 coin |

|

103-76 B.C.E. |

Jewish |

Alexander Jannaeus |

143 coins |

|

76-67 B.C.E. |

Jewish |

Alexandra Salome

and Hyrcanus II |

1 coin |

|

63-40 B.C.E. |

Jewish |

Hyrcanus II |

5 coins |

|

40-37 B.C.E. |

Jewish |

Antigonus Archelaus |

4 coins |

|

37-4 B.C.E. |

Jewish |

Herod the Great |

10 coins |

|

4 B.C.E.-6 C.E. |

Jewish |

Herod Archelaus |

16 coins |

|

41-44 C.E. |

Roman |

Agrippa I |

78 coins |

|

41-68 C.E. |

Roman |

Procuratorial Period |

91 coins (46 from Nero's reign, 54-68C.E.; 13 of

these found above level of ash otherwise dated to 68 C.E.) |

|

66-68 C.E. |

Jewish |

First Jewish Revolt |

0 from Year 1 (66 C.E.)

83 from Year 2

5 from Year 3

0 from Year 4 (69 C.E.) |

|

132-135 C.E. |

Jewish |

Second Jewish Revolt |

2-3 coins |

Question

#1. Based on the above evidence, determine the period of occupation

of the Qumran site. Account for variations in the numbers of coins found

in particular periods. Can you make any educated guesses about the period

from 68 B.C.E.-135 C.E. (note denominations

of coins and gaps in coin evidence, which suggest periods when the site

was not occupied and therefore a subsequent change in occupants). Question

#1. Based on the above evidence, determine the period of occupation

of the Qumran site. Account for variations in the numbers of coins found

in particular periods. Can you make any educated guesses about the period

from 68 B.C.E.-135 C.E. (note denominations

of coins and gaps in coin evidence, which suggest periods when the site

was not occupied and therefore a subsequent change in occupants).

1

"Fouille au Khirbet Qumrân," Revue Biblique

(hereafter RB) 60 (1953) 83-106; "Fouilles au Khirbet Qumrân,"

RB 61 (1954) 206-36; and "Fouilles de Khirbet Qumrân,"

RB 63 (1956) 533-77.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|