Capote had a fairly consistent writing pattern throughout his career. He read and wrote constantly. He would disappear for a while, to his beach house in Long Island or his chalet in Switzerland, write, and then come back to public view in New York, socializing at dinners and parties (Steinem 86). Capote would spend hours on structure or single paragraphs. He was always revising, but when he declared a piece finished, he was “convinced that it was as good as it could be, and few could shake his confidence” (Clarke 223-24). Part of this confidence was in Capote’s characters. He developed them in such a way that he knew where they “were going and what they would do when they got there” (Clarke 223). He could not understand how an author could just write without knowing what was going to happen to his or her characters. Capote never made any deadlines for his works, he simply just wrote until it was finished, and then sent it to the publisher (Steinem 91). Many also praised him for his ability to tell a great story, and then still be able to write it down later, and make it just as admirable (Breit 18). While each of Capote’s stories were different, there were some common themes that surfaced throughout his career. These included fear, loneliness, the struggle to find a place in the world, hidden homosexuality, self-hatred, and rage at the world (Garson 70). These themes paralleled difficulties that Capote faced in both his younger years and in the present. Much of the fear and struggle came from his constant battle with his sexuality, his lack of strong family support, and his desire to find where he belonged.

For Capote, writing was an art. He felt that the “greatest pleasure about writing is not what it’s about, but the inner music that words make” (Steinem 88). This described Truman’s work perfectly; his stories were interesting, yet it was the interpretations and insights the reader gained that made them into great literature. His style was both “closeted” and “uncloseted” when it came to writing about homosexuality. It was “closeted” in the sense that, with the exception of Other Voices, Other Rooms, he did not overtly talk about homosexuality. However, his work can also be considered “uncloseted” because his “code for homosexual interpretations was so easily seen through” (Dukes 2). For instance, in Capote’s famous Breakfast at Tiffany’s, neither the protagonist, Holly Golightley, nor any other characters are portrayed as homosexuals. Nevertheless, Capote wrote many women characters, such as Holly, in such a manner that they represented the desires of gay men (Dukes 142). Not only were they very feminine, but their hopes and dreams symbolized those of both Capote and other homosexuals in New York. Like most homosexuals, Holly desires a life in New York in which she belongs, in which she has a specific place in society. |

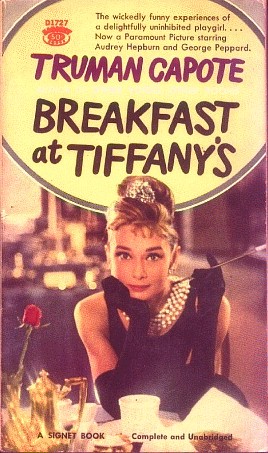

Source: "Truman Capote." Browne Popular Culture. Publisher: Signet

|

Besides underlying tones of homosexuality, Capote’s works are important because they provide the public insight into the author’s own life and struggles. Many of his characters either parallel himself or people, particularly ones he had conflicts with. For instance, in “My Side of the Matter” two of the characters represent the aunts he lived with from age four to ten (Robinson 8), while “A Christmas Memory” is partly adapted from his own childhood reminiscences (“Capote, Truman” 445). Even in his adulthood, he could not escape the pain his family caused him, or the difficulties he faced in his life. Some of his stories also incorporate influences in his life that were not based on the troubles of his past, but on his positive relationships in the present. The Grass Harp is a story about two sisters who are fighting over the family business. Capote writes the two characters based on his affection for two friends, Dolly Talboo and Catherine Creek (“Capote, Truman” 444-45). While most of his stories also integrated aspects of his own life and personality, there is one story in particular whose protagonist he most visibly identifies with.

One of Capote’s most famous works, Other Voices, Other Rooms is certainly the one that most clearly deals with issues of homosexuality, and is the most important to discuss when examining his works’ impact on the queer community. Perhaps why it was so successful is that Capote “knew exactly the effects he wanted” to make with this novel (Inge 45). He wanted to “urge the audience to a better understanding and deeper acceptance of homosexuality through a groundbreaking treatment of adolescent gay identity” (Pugh 1). He accomplished this through the many parallels between his main character’s and his own story. The main character, Joel, must cope with a deceased mother, a father who is in a coma, and aunts who do not care for him (Garson 69). This parallels Capote's life, as mentioned previously, because his mother committed suicide, he had no strong relationship with his father, and he lived with his mother’s sisters for a number of years as a child. When the book was published in 1948, he stated that it was a story about “this bright moment…when [Joel] gives up his boyhood” (Inge 6-7). The characters in this story cannot escape from the world they live in and must find their true identities “not by a retreat into heterosexuality, but through an acceptance of their homosexuality” (Pugh 3), just as Capote was forced to accept his sexuality at a young age and continue to fight for it throughout his life.

Capote sends a powerful message through this novel by creating a hero who is not a heterosexual but rather a “gay adolescent hero.” Many argue that Other Voices, Other Rooms is merely a Southern gothic novel, but having a homosexual hero suggests that “the sentimentalism at the heart of his project [had] specifically queer objectives” (Pugh 1). The hero struggles through a nightmare world, as Capote had done in his life, in order to accept and bring others to accept his homosexuality. The character Joel, as well as others in the novel, Capote wrote as the “representations of the way people ought to be if only the world would let them be so” stressing that “love of any kind should be prized” (Pugh1-2). Thus Capote’s novel was not merely Southern gothic, but also sentimental. Through a fascinating and well written story, Capote reveals parts of himself to the outside world through the protagonist, while expressing the importance of accepting homosexuality into society.

Capote’s writing began to dwindle in his later years. He did not produce much in the last decade of his life. His last works are considered to be the short story “One Christmas” and the novel Answered Prayers. Capote had worked on Answered Prayers since 1958. It was supposed to be his masterpiece, but he never finished it (Garson 78). The four short stories published in Esquire from 1975-1976 were intended to be part of this final novel. However, “Mojave” eventually became part of Music for Chameleons when it was published in 1980. When the other three stories appeared in Esquire, many found them offensive and were hurt by them. This marked the end of his career as Capote’s reputation as an admirable member of societywas somewhat destroyed by them. These three stories, Unspoiled Monsters, La Cote Basque, and Kate McCloud were published in Answered Prayers in 1987 after Capote’s death (Garson 78-9).

Capote’s works varied not only in type (from short stories to screenplays and novels), but also in style and issues. He wrote about murder, love, and life in New York. Many of the common themes and underlying messages of fear, loneliness, and acceptance of homosexuality appeared throughout his work. Furthermore, much of himself and his life were revealed in the characters created; his struggles paralleled many of theirs. Many of his relationships from his childhood and young adulthood also appeared in his novels. Capote hoped that his works would reach readers on a level that allowed them to better understand him and the world he lived in, as he stated that “the ‘message’ of a story should be after all the story itself” (“Capote, Truman” 444).

Highlights and Most Well-known Works

1943: “The Walls are Cold”- first short story Capote wrote at age 19. Published in Decade of Short Stories.

1945: “Miriam”-short story published in Mademoiselle. Won an O Henry Memorial Award.

“My Side of the Matter” published.

1946: “The Headless Hawk”-short story published in Harper’s Bazaar, and selected to be included in The Best American Short Stories 1947. “Jug of Silver” also published.

1947: “Shut a Final Door”-published in the Atlantic. Received an O Henry Award.

1948: Other Voices, Other Rooms published. This is Capote’s first novel, and considered the only

one that is openly about homosexuality.

1949: The Grass Harp published. Stage version open on Broadway in 1952.

1958: Breakfast at Tiffany’s, a novella, published.

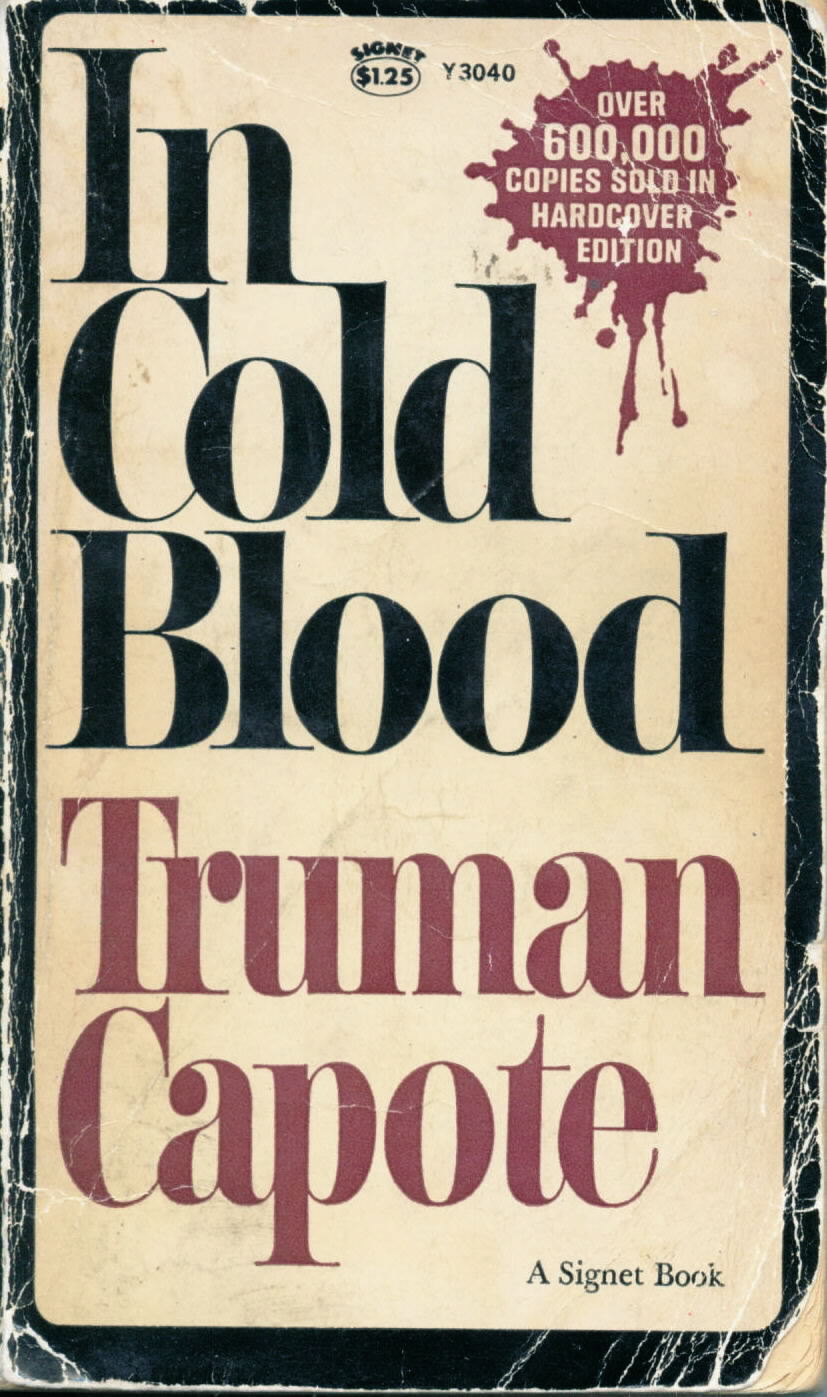

1966: In Cold Blood published. The height of Capote’s fame and fortune. A grim account of the Clutter family murders in Holcomb, Kansas. Capote went to Kansas to research for the novel, and became fascinated with the lives of the murderers, Perry Smith and Richard Hickock. He then developed the novel to work to better understand those two. He wrote to each of them for the five years they were in prison, as well as interviewed other criminals. Film version released in 1967.

“A Christmas Memory” published. Won an Emmy Award in 1967. Eventually adapted for

television.

1968: “The Thanksgiving Visitor” published.

1972: "Truman Capote Behind Prison Walls" premiered on ABC television. A ninety-minute

documentary on criminals inspired by his research for In Cold Blood.

1975: Mojave and La Cote Basque, 1965 published in the Esquire. Mojave was the first piece of fiction Capote had written in eight years, and was supposed to be the second chapter of Answered Prayers, but instead became part of Music for Chameleons.

1976: Unspoiled Monsters and Kate McCloud published in Esquire.

Play role of Lionel Twain in Murder by Death

1980: Music for Chameleons published. This was a work that was comprised of many pieces he

had written for magazines. Capote dedicated the novel to Tennessee Williams.

1987: Answered Prayers published after Capote’s death. Unfinished, it contained the four short

stories published in Esquire from 1975-76.

Scripts:

Beat the Devil

The Innocents

Trilogy |

Source: "In Cold Blood: Truman Capote's Classic..." Publisher: Signet

|

|

|

|